Harvard University

Humankind has always strived for a reach that exceeds its grasp, and since time immemorial we’ve pushed past our limitations with the help of

Gadgets!

From either the French word for "lock mechanism" or "tool" we now think of gadgets as tangible ways that scientific research is made manifest in our lives.

Ripeness tester

A team of students from the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences tackled the complex problem of avocado ripeness as their project in “Engineering Problem Solving and Design Project.”

Stirred pressure vessel

These vessels mimic deep-sea geothermal vents, allowing biologists to study the habitable limits of life on Earth and to explore the potential of life on other ocean worlds.

Airbag for cyclists

Ethan Seder engineered this device to electronically detect an accident, release a gas, and quickly inflate a textile airbag to protect the upper torso of bikers.

Tentacle grabber

Taking inspiration from nature, Harvard researchers designed a new type of soft, robotic gripper that uses a collection of thin tentacles to entangle and ensnare objects, similar to how jellyfish collect stunned prey. Alone, individual tentacles, or filaments, are weak. But together, the collection of filaments can grasp and securely hold heavy and oddly shaped objects.

History at hand

This timeline, sprinkled throughout the page, explores ingenious gadgets and devices from historical collections all across Harvard.

Built around 1550

Planispheric astrolabe

The astrolabe was a multi-purpose tool, which served as a sky map, timepiece, astronomical computer, navigational aid, and surveying instrument. It was invented sometime before the fourth century CE, although the mathematics that underlies it was known in Greek circles 400 years earlier.

Learn more at the Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments

Built in 1636

Rectangular ivory diptych sundial

The ivory diptych sundial was a time-finding tool of the early modern period, which could be conveniently carried in a pocket. The example shown here was adjustable for use in different latitudes from 42° and 54°. The sundial included a wind vane, magnetic compass, a list of cities and their latitudes, and several different types of vertical and horizontal sundials that not only found the time in three different hour systems but also the lengths of day and night and the Sun’s place in the Zodiac throughout the year.

Learn more at the Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments

Animal-inspired robots

Octobot

This robot has no hard components, no computer, and no battery. It uses logic and chemical reactions to inflate the actuators and move the limbs.

RoboBee

This robot is half the size of a paper clip, weighs less that one-tenth of a gram, and flies using “artificial muscles” compromised of materials that contract when a voltage is applied.

TunaBot

This robot can accurately mimic both the highly efficient swimming style of tuna and their high speed.

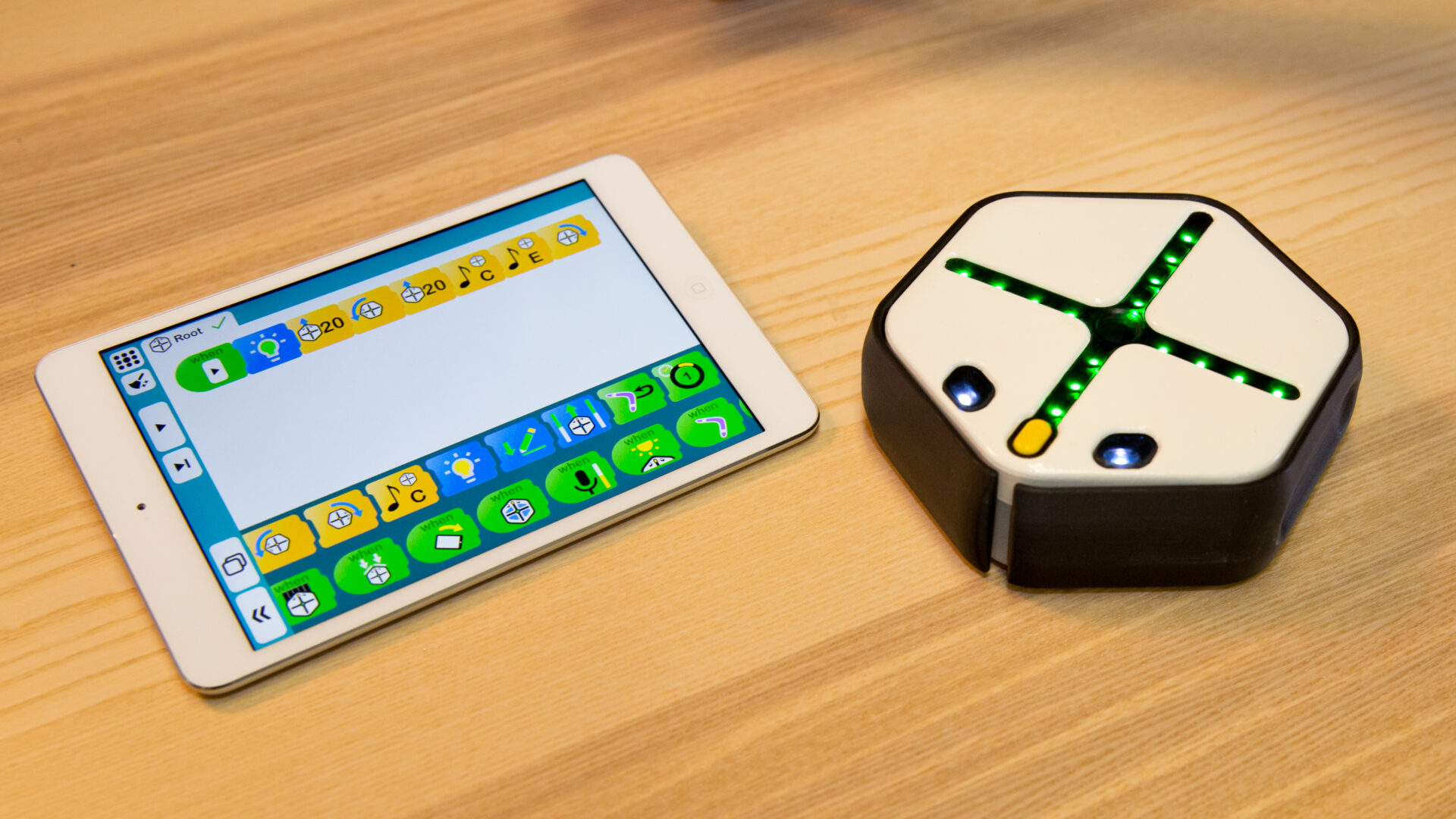

Educational coding robot

Root Robotics’ educational Root coding robot got its start as a summer research project at the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering in 2011 and subsequently developed into a robust learning tool that is being used in over 500 schools to teach children between the ages of 4 and 12 how to code in an engaging, intuitive way.

Built in 1837

Cupping set

Cupping sets were used for a form of alternative medicine that involved creating suction on the skin with the application of heated cups.

Built in 1968

Myoelectric elbow

Dubbed the Boston Arm, it activated when the wearer tried to move their missing lower arm. The biceps or triceps muscle in their residual limb generated a faint electrical signal that was amplified by electrodes taped to the skin and sent to a motor inside the prosthesis. The motor, powered by a battery pack worn on a belt, turned a screw that bent or straightened the artificial elbow.

See the world differently

Laser-scanning microscope

Bernardo Sabatini, professor of neurobiology, builds imaging devices because it’s fun and because he’s frustrated by questions about the brain he can’t answer with existing technologies.

Fluorescence microscopy

In this LabXchange video, Harvard specialist Erin Diel takes us into the lab to demonstrate the power of using fluorescence microscopy to study cell biology.

Cryo-electron microscope

Cryo-EM, which involves flash freezing molecules and imaging them with an electron microscope to deduce their structure, opened a door to a new world of biological insight.

Celebrity-scopes

There’s a saying in the Loparo lab: You don’t do experiments on Chuck Norris; Chuck Norris does experiments on you. In this case, Norris refers not to the Hollywood action hero but to a custom-built microscope named after him.

Norris and his brethren—including Robocop, Rambo, the Buffybot, and B.A. Baracus—help Joe Loparo and his team in the Blavatnik Institute at Harvard Medical School reveal how cells duplicate DNA and tolerate or repair DNA damage.

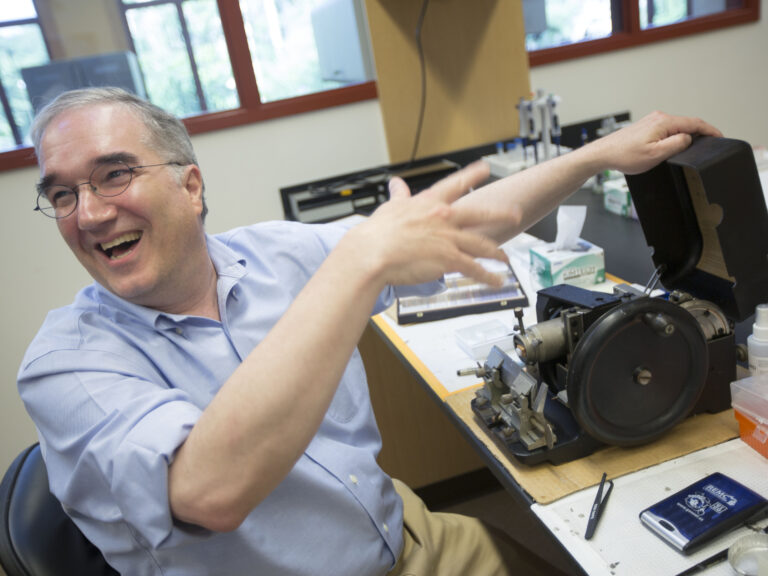

Built in 1931

Microtome tissue slicer

Manufactured in 1931, Arboretum director William “Ned” Friedman is in no hurry to replace this tissue slicer, which shaves off extremely thin slices of plant or animal material so they can be viewed under a microscope.

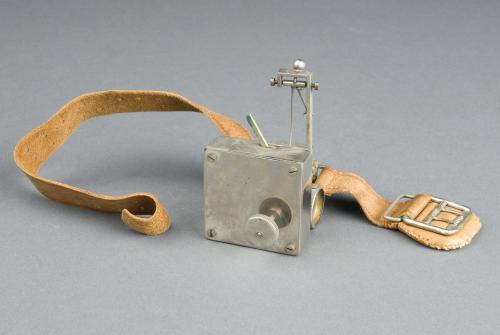

Built in 1890

Sphygmograph

This instrument would attach to the wrist and record the pulse as waves on recording paper.

The art and science of restoration

The Harvard Art Museums uses a number of devices to assist them in restoring and displaying their collections.

Microfader

The Harvard Art Museums’ conservation staff use the microfader to measure objects’ light sensitivity, which in turn enables them to make informed decisions about when and for how long to place light-sensitive objects on view.

Laser

“We don’t use the laser all that often, but when we do, it’s just so amazing,” said Susan Costello, associate conservator of objects and sculpture. “It can remove grime very evenly and quickly.”

Projector

To restore several Rothko paintings to their original, unfaded color, scientists projected compensation images onto the faded canvases.